A Fictional Tribute to American “War Dogs” in Vietnam

On muddy bellies, Dog-Handler Private 1st class Henderson and Bomb-Sniffer Dog Buster both carefully crawled through the darkness of winding Vietnamese tunnels. The tan and black German Shepherd led, ignoring the long jungle roots that sometimes broke through above and scraped along his back. Henderson watched his dog, alert for the canine’s body language that would signal any kind of explosive booby-trap.

Then the two would cautiously trade places–if the tunnel allowed it–canine in back, human in front as Harry Henderson gingerly disarmed the Kong surprise. Like now. Buster froze, even his panting stopping as he signaled, Got one for yah, Dad! Aren’t I a good boy, Dad? We get to play later, right, Dad? Get that sucker and we go home, right Dad?

The men safely waiting outside the tunnel used to make fun of Henderson, calling him a homo fairy for talking baby talk to the dog. “Come to Daddy, buddy boy. Be a good boy for Daddy. Find the bomb, screw the Kong. Right, baby? Screw the Kong, find the bomb.”

That was Henderson’s good luck chant before every mission. He made everyone he led say it twice, forwards and backwards. One sergeant, a bile-ridden lifer who hated Henderson’s Midwest nineteen-year-old white ass and freckled cheeks, hated the baby talk even more. Called Henderson names with foul language Henderson didn’t even know existed until he was drafted and became half of the Double D. That’s what everyone called him, short for Dog and Dogface cornhusker. Henderson wasn’t a corn farmer, he was a fourth generation raiser of dairy cows. In fact, he almost got out of being drafted, but there was plenty of other family working the farm, and he had to mobilize after all. Okay, so he was slow with books, but he could read, couldn’t he? Some of the other soldiers couldn’t. And he wasn’t gay! He had married his high school sweetheart the week before he left. He even showed the sergeant the most recent photo of his pregnant, seventeen-year old wife Jan.

“We marry early on farms, you know,” he told Sarge.

The Sergeant called Henderson’s wife the foulest thing Henderson had ever heard in his life. That day he refused to work Buster on the mission. Said unless the Sergeant apologized for what he said about Jan, and said, “Screw the Kong, Find the Bomb, Find the Bomb, Screw the Kong,” he wasn’t moving. Then Henderson sat down on the muddy, bug-ridden, foul stench of land that was jungle and didn’t move. The Sergeant lifted his handgun with a dangerous look in his eyes, but Henderson’s buddies quickly crowded around him.

“Eff this,” the Sergeant spat out. “Come on, men, let’s leave this pansy and his puppy behind.”

Twenty-five minutes later it was raining Sergeant body parts all over, along with anyone else stupid enough to leave the Double D’s side. From that time on, no one called Henderson names, even though Dogface was a traditional Army name. They decided growing up on a farm with the animals made Henderson a magician with the dog. Agreed his wife was the most beautiful pregnant woman they’d ever seen. And no one, but no one, ever failed to say the magic chant forwards and backwards before every mission.

Henderson had luck. Good, better, best mojo in the world. Big swinging cajones, the others said. Henderson didn’t know what cajones were, but he kept on living when the other dog handlers and their partners didn’t. Sometimes the dogs didn’t keep still enough when they signaled and blew themselves and their handlers to smithereens. Sometimes the handler screwed up disarming the bomb and blew them up. Sometimes the Kong shot the handler. Sometimes the Kong shot the dog. Sometimes the leftovers teamed up with leftovers and didn’t work as well and blew everyone in their squads up. Sometimes the booby traps were bamboo spears and machetes and the dogs didn’t smell any incendiary or explosive device. And sometimes shit happened.

That’s what everyone said. Shit happened, but not to the lucky Double-D team. Nothing went wrong. Not one thing. Henderson knew Buster was his ticket home. Buster got fed first, watered first, cleaned up first, slept first. Henderson never left the dog’s side, he even took Buster with him into the latrines. Three and a half more months and he headed home to see his new wife, and newer baby boy. One of the guys drew a grid of 100 boxes on a naked Playboy pinup, and told Henderson to start x-ing them out, one every night. Henderson blushed, his freckles burning, when he saw where the squares for the final three days were located.

“But you put two of them right on her teats!” he said, for breasts and nipples would always be udders and teats to him. “And the last square is right on her…good Lord!”

The story got around, and most of the guys laughed and clapped him on the back, trying to explain that the “last box” went on the “best box,” so to speak. Henderson didn’t get it. His buddies explained the pun, and added that they’d miss him when he went home.

Some A-hole Lieutenant spoke up. “Too bad your dog won’t be coming with you.”

Henderson had blinked in surprise. “What do mean, Ell-Tee?”

“He stays behind, just like the other dogs. He works ’til he dies. One day that fuzzball will be raining blood and guts all over, just like Sarge. Or the VC will shoot him dead and slice him up for dinner. They eat dog on a stick. Or the war ends, you shoot your dog in the head, then go home.”

Henderson hadn’t believed it. Couldn’t believe it. When he checked and found it to be true, he spent the night puking into his helmet. Buster whined, and pushed his black nose and tan ears under his arm, trying to comfort his handler. Henderson puked until he couldn’t puke any more. Then he sat in his tent with his dog for two days, not eating, not sleeping, not moving except to tend to the dog’s needs and petting the dog’s black and tan head over and over and over. The officers called the medic, then the doc himself. Henderson wasn’t faking it, the doc said. Henderson might need a shrink visit or two.

Someone screwed with his head. Did anyone know who it was, and what was said? No one spoke up, but Ell-Tee showed up the next morning with two black eyes and a broken rib. Of the next party that went out on tunnel duty without the Double-D, only half came back breathing. The rest were in pieces, except for the Ell-Tee, who was still intact but just as dead outside the blown tunnel with a bullet in his head. No one bothered to do an autopsy to see if it was a Charlie or American slug. Everyone knew…except Henderson, who sat quietly in his tent, his arms around his partner.

The next team ordered tunnel duty refused to search for a still-missing cache of stolen American munitions that intelligence swore hadn’t left the area, at least, not yet. The tunnel men said unless Henderson went, they weren’t moving anything but their trigger finger. The frightened C.O. went to Henderson and swore that if Henderson went back to work, he’d cut papers allowing the dog to go home with him. Henderson believed him, but his buddies didn’t.

“Make the shithead show you the papers,” they told him, bringing more food and water for Buster and some for Henderson himself. “Make sure that they’re signed by a Colonel, at least. Hell, go for an effing General. Don’t trust him, man. Leave it to us. We’ll look after our Double-D.”

Two days later Henderson had his papers. He took his wife and new son’s photo out of a special waterproof pouch, replaced them with Buster’s paperwork, then put them around his dog’s neck, and taped the zipper closed so Charlie wouldn’t hear metal against metal. Buster didn’t like the pouch. He started to scratch and fuss at it until Henderson barked out as sharp a command as he’d ever given. Buster froze, accepted the order, and a few minutes later buried his soft bomb-sniffing nose in Henderson’s lap.

“I’m sorry I had to yell at you, boy, but it’s for your own good,” Henderson crooned, scratching the big black triangle ears. “I promise I won’t ever leave you alone. You got my word on that. You take care of me, I take care of you. That’s our deal. Come on, let’s go scratch one more square off that naked lady the guys gave us.”

The lady never had her three private areas marked with black. Long before her legs and arms were even half covered, the war was over. His whole unit was trucked to Saigon as support personnel, but then the NVA started to overrun Vietnam and everything went to hell. Everyone went scrambling for safety, and suddenly men were fighting to get on helicopters, and soldiers were fighting to get to planes, and dark-skinned girlfriends with blue-eyed babies were crying.

Henderson loaded his pack with food and water for himself and his dog, looped the leash through one hand, slung his rifle over his shoulder, and he and Buster headed for the planes amidst shells and firing and reports and chaos. The truck evac driver didn’t want Buster in the truck bed.

“Essential personnel only!” he ordered.

The three remaining buddies who had come to ‘Nam with Henderson were now expert strategists and just as superstitious as Henderson about Buster being their lucky ticket home. They convinced the driver otherwise when he refused to honor Henderson’s papers–papers he claimed were phonies.

One, a native Apache from Arizona, said Buster was an Army soldier. The quiet Dakota kid said there could be bombs in the road and they would need him. The handsome young Latino from LA simply held a pistol to the man’s head, and kept it there for the whole ride to the airport. He demanded that the Double-D be admitted through security or else.

“You’d kill me, an American?” the driver asked as Henderson, dog, and buddies gathered around the truck while others fought the mobs to get to the plane.

“My country had me killing women. As for killing my own, friendly fire killed my cousin. The last man I killed was a U.S. of effing A. bastard who tried to take my lucky charm away from my lucky bud. If the Double-D doesn’t get on the plane, you’re going home in a body bag, asshole. Now repeat after me. Find the bomb, kill the Kong. Kill the Kong, find the bomb.”

The driver took one look at the Latino’s eyes, took in the mass of chaos exploding above, around and behind him and said the chant, followed by, “We’re all getting on that plane. I just quit the limo biz.” Leaving the keys in the ignition and the truck’s engine still running, they ran for the plane; the driver’s airport security clearance and Buster’s waterproof pouch getting the five men and dog aboard.

They barely made it off the ground amidst all the explosions.

“Son of a bitch, look at it!” said the Quiet Kid at the window. “The whole damn world’s gone mad!”

“There’s women and kids down there running after us!” the Apache said. “They’re running after our effing plane!”

The Latino, still suspicious of the driver, kept his eyes and gun on the fifth man. “There better not be any Army dogs out there,” he said, fingering his weapon. The driver shivered.

Henderson refused to look. He buried his face in the thick, heavy fur on his panting dog, and prayed they would make it home alive.

Deadly, manmade hell rained on the plane at the first stop, a quickie fuel run while still in country. Most of the soldiers absolutely, and wisely, refused to get off the plane. Henderson’s buddies surrounded him and Buster, for Henderson wanted to get off to walk the dog and let him relieve himself.

“He can piss on my shoes if he has to,” the Apache said.

“Better yet, he can shit on this candy-assed driver,” the Latino said. “You stand up to get off this plane, I’ll shoot you in the effing leg, I swear.”

The other two looked at Henderson. “You know he’ll do it,” they said.

Henderson knew. “I’ll stay. But I gotta go, too.”

“Who’s got an empty canteen?”

The driver immediately shoved his almost-emptied canteen their way. “Take mine. That dog of yours can use it too, if you can catch it.”

They couldn’t catch it, nor could anyone else, for the fighting and explosives continued even more heavily than before. By the time the plane landed at the second, safe stop thirteen hours later, the airplane stank of more than just urine from man or beast. Some of the men, mostly the bachelors and drug-addicted–disembarked to be processed and fed and washed. The wounded were carried out. The rest, married men with families, men too afraid to move, and men who weren’t about to follow one more Army order despite the smell of blood, vomit, and body wastes remained aboard, or fought to get on other transfer flights with toilets for the final flight to San Francisco.

“Jesu Christo, I see home!” the Latino cried a long while later, looking out at the California coast far below. “I’m gonna kiss the ground, go to church, and screw my old lady silly.”

“Not necessarily in that order,” the Quiet Kid snickered, his first words in hours.

The men grinned, grabbed a piece of dog and held on as the plane began to descend. “Gotta say it one more time for a safe landing,” the Apache ordered.

The others, including the driver and everyone else on the plane within hearing distance, chanted the words forward and backward.

“You know, our local natives aren’t as superstitious,” Henderson said, holding tight to Buster.

“What do those damn buffalo eaters know, anyway?” The Apache laughed, the first time he’d laughed since leaving Arizona over a year ago. The plane landed with a bump and a jolt.

“Hey, Henderson, I want some of your dog’s fur to take home with me. Can I pull some for luck?” the Latino asked.

“Take some dog turds instead,” the driver muttered, who’d been forced into shit brigade for Buster.

Everyone laughed again, for they were now safe. “We get off here,” the Latino announced. “Remember, we four stay in touch. Everyone got their address list? Okay, vamanous! We meet up later when everything’s squared away, si‘?”

Buster and Henderson were the last ones of the group to make it home, thanks to a stateside admin idiot who’d never seen a rice paddy. He insisted Buster be quarantined. Henderson argued, pleaded, and finally escaped with his partner from the base. The Double-D hitchhiked home. Vietnam vets were scum to the public, but animal lovers still abounded. Even women trusted a man with a dog, and he found lots of rides. The Army could finish his paperwork/discharge without him. He got his discharge by mail, and read it in front of his home mailbox, his body all in one piece.

Well, physically in one piece, his young wife and parents said. Henderson couldn’t adjust to his old farm life. PTSD, the doctors said. No one had ever heard the new fancy name for shell shock. The docs explained, and urged him to go to the VA for counseling. Henderson refused. The military was after his dog, he said. He’d kill anyone coming after his dog.

His wife, young but terrified of losing her husband, didn’t push the issue. She tended their young son Billy, and worked the cows along with everyone else on the farm except Henderson. He didn’t know what to do, and neither did Buster. Life seemed so strange after ‘Nam. His mother started nagging. His father sermonized about his Korean days. His wife Jan cried. Everyone said Jan would walk if he didn’t straighten out.

He tried, he really did. But it was only when he brushed Buster’s black and tan coat, stroked the silky fur, and worked their daily exercises that he felt alive. He hid ammo around the farm, then he and Buster would do searches for “contraband.” Jan said maybe he should try to get into the police force, work the bomb squad in the city. Her parents started nagging her, but Jan refused to side with them.

For a moment, Henderson almost felt his old affection for her come back. He smiled, and got out his old suit for her to iron. It was too big for him. He’d lost weight, but didn’t care in the excitement. Jan offered to drive with him to Kansas City, but he refused. He and Buster would make the trip alone. Later, he felt bad he’d denied her the trip, for he had no good news for her.

“I couldn’t pass the psych eval,” he said. “They all think I’m psycho.”

“What do they know? Maybe you should go to that VA counseling group…not because you need it,” Jan said quickly. “But that way you’ll figure out how to beat the system.”

Henderson kissed his wife in gratitude, then in passion. They made love that night, and the next, for sex wasn’t something he had much interest in anymore, but a man had to do right by his woman. Right?

He started doing the VA’s PTSD meetings, Buster coming along in the car for each trip. Henderson couldn’t bear to be separated from Buster. After four months the counselor told him to quit screwing around and start facing his demons, or stay home. Henderson spit on the shrink’s linoleum floor, something he’d never done in his life, and drove back to the farm, Buster’s nose on his shoulder.

At home, he went into the big dairy barn with its strong, yet comforting smell of cow, and cried like he hadn’t ever cried before. He sobbed for the uselessness of the war, for the men and women and kids and dogs who had lost their lives, or a year of their lives, or their legs, or arms, or minds, like him. He cried so hard he lost his voice, and still he sobbed until the ever-faithful Jan came out to see him. For once he concentrated on her instead of Buster, his touchstone.

“I’m a loser, Jan. A fruitcake. I think you should let your parents get that divorce lawyer. You deserve a better husband and a real father for the boy. I can’t do it. I swear I’ve tried. I can’t.”

Jan said nothing. She went back into the house, and brought him his reheated dinner with foil over the top, a thermos of coffee, and Buster’s bowl with Purina chunks and leftovers. “Eat up,” she said. “I’ll be in bed. Kiss your son goodnight later, please.”

Her lack of tears, anger, anything bothered him. How could she be so calm when his life was falling apart?

For her sake, and the boy’s–he never thought of his son by name like he did Buster–he forced himself back into his old routine. He got up with the cows and came home with the cows. He worked with in-laws and parents and friends and even worked hard with that patronizing VA effing shrink, although he never used either the “f” or “s” word around home. He and Buster were still as close. He just couldn’t allow others into the safe zone that he only felt with Buster at his side.

He even tried to work with the public and the military and the A.S.P.C.A. about the plight of war dogs. Ever since WW2 canines had been abandoned or destroyed during peacetime, first in Europe, then Korea, now ‘Nam. It wasn’t right. They were soldiers too, weren’t they? For awhile he had some support, even some publicity, but then came the POW planeloads, and the orphan planeloads, and more POWs and more orphans, and then the question if that were really all the POWs, and what about the MIAs? The war dog rescue effort faded into the background. Even Henderson knew it was a lost cause.

But that was okay. He got his own dog out. He’d kept his promise never to leave his four-footed buddy behind, thanks to his three human buddies. At least they were doing better than he was.

Everyone kept their promise to keep in touch. Henderson learned that the Quiet Kid got religion in those ‘Nam foxholes. He decided to cash in on his listening skills, and started schooling to become a preacher. The Latino decided to stay in for the free medical and housing, his Catholic wife keep popping out the ninos, and the Latino decided he could handle being a soldier in peacetime. He’d always been an ace with weapons. The Apache, a family man before the war and even more so afterwards, learned terminal ovarian cancer was preventing the children he and his wife both wanted. His Tucson wife put the Apache’s gun to her head and ended it. When her husband discovered her body, he tried to join her, but the wife had thought of that, and hidden all his other ammunition. By the time he found it, the police had arrived.

Henderson drove with Buster to the funeral. The Latino and Quiet Kid both showed up as well. Afterwards, the Latino brought the Apache to California, fixed him up with some young mamacita; a fertile, willing cousin who let the Apache get her pregnant. The Apache married her and flew back to Arizona with his new bride. Last Henderson heard, they’d opened up some taco and beer cantina on the Tucson border, were raising the baby, and the wife was happily knocked up again.

Henderson enjoyed their good news, and wished he had some of his own to share. He never did, though, and although their letters kept coming, he rarely mailed much beyond a postcard. Still, his pioneer ancestor blood refused to give up trying for the stability his buddies seemed to have found. He forced himself into the role of civilian husband. For a while, it seemed to work. Every night he would even sit down and read the paper like his father and his father’s father had done, while Jan worked on her correspondence courses in farm accounting, and little Billy, now almost three, played after his bath. He didn’t really feel like his old self, but Jan cried less and God Almighty that was a relief. It seemed much harder to force himself to be a father. With all the other family men around daily on the huge farm, Henderson didn’t feel that guilty. The boy deserved better than a screw-up like himself. Still, he was as kind to the child as he could be.

Buster would lay on the rug near the boy, then trot over to Henderson to lick his hand as if to say, “You’re still my favorite, Dad. I’m just amusing myself until you’re done, Dad.”

Henderson would talk babytalk to the Shepherd, love in his voice, fondness in his touch.

“I wish you’d work more with Billy than that dog,” Jan said impatiently. “He’s almost three years old and still crawls. Mom says I should take him to the pediatrician if he won’t stay off the floor.”

Henderson tuned out her witchy tone that seemed to be coming more and more these days. “The boy will walk when he’s ready.”

“And stop calling him the boy! His name is Billy!”

At that moment, Billy picked up Buster’s rubber bone in his mouth, crawled over to Henderson, dropped the bone at his father’s feet, and licked his father’s hand as Buster had done so many times before. Automatically Henderson’s hand dropped to ruffle canine fur, only to feel the silky baby blonde of his son’s instead. At that moment Billy whined in contentment, so exact an echo of the dog that Buster’s pointed ears pricked even higher on his head.

Jan stood up, her face white. Her pencil and paper slid to the floor. She left them there. “I want a divorce.” She lifted Billy into her arms, went upstairs, put him to bed, and started to pack some things for her son and herself. Henderson stopped her.

“This is your home. I’ll sign the house over to you and the boy–Billy,” he remembered to say, but Jan’s expression showed he was too late. “I’ll stay with Mom, and come get the rest of my things tomorrow.” He took the suitcase from her hand, and then gently touched her hair.

“You tell our son that none of this was your fault, or his. It’s mine. If it wasn’t for Buster, I would have hung myself in the barn months ago.”

Jan started crying, reached for him, pulled him into what was once their marriage bed for a night of desperate passion…and the last time they ever made love.

The divorce went through without fuss, and without acrimony. Henderson moved into an empty room in his grandmother’s house, Buster in tow. He continued to work the dairy farm for two years until Jan starting dating someone whose farmland adjoined the Henderson land. Then he reapplied to the police for K-9 bomb duty. This time he passed the psych eval. The police were reluctant to take on what they considered an “outside dog,” but when Henderson asked for testing for Buster, they changed their mind. He and Buster both passed K-9 training with flying colors. Henderson moved in with another policeman with no canine and a big yard.

Jan’s new husband Chet–a nice guy Henderson still hated–came over to say that Jan worried about him, and so did Billy, now a walking, talking child who lived for his father’s weekend visits. Chet wanted to adopt Billy and give him a new last name.

“Jan doesn’t know I’m asking, but I thought what with your job and all, it’d be the sensible thing to do in case, well, you know. You are a cop.”

Henderson held on tight to Buster’s leash with two hands, and managed not to punch out the guy’s lights. “You can adopt him after I’m dead, and not before. Not that I’m planning on buyin’ it anytime soon.”

Chet said he understood, invited him to Billy’s fifth birthday party in a few months, and on his way to the car, threw out the fact that Jan was pregnant. Henderson wished he was back in ‘Nam with Chet for just the two seconds it would take to unholster his gun and blow the bastard’s brains out. Then he pushed those thoughts aside and climbed back into his squad car, Buster in the seat behind him.

Three months later he bought his son a huge green John Deere tractor with pedals and chain like a tricycle, and drove out past the old quarry toward the home of Jan’s new in-laws. Four generations of Hendersons couldn’t get Billy interested in dairy farming, but the boy treasured everything his father gave him. Maybe the tractor would earn him a few brownie points with Jan. Unlike when she’d carried Billy, she’d turned sour and bitchy for this pregnancy. The old in-laws blamed the new husband’s “bad seed.”

Henderson just hoped Billy would love his new sister or brother. The boy never did take a shine to his stepfather and continued to worship his real father, something that made Jan even bitchier. His old mom-in-law said she wasn’t really happy with nice guy Chet. His old brother-in-law said the bastard probably stunk in bed. His grandmother said all Billy talked about was being a cop, “Just like Dad.”

Nice boys who’d never been to war belonged with family on the farm, they insisted, not with criminals trying to maim and kill others with bombs. And so, the tractor with a birthday bow, now hidden under a blanket in his trunk.

He drove out to the party at Jan’s new mom-in-law’s farm on Billy’s birthday. He wouldn’t stay long, just long enough to drop off the gift, for he was working a double shift. Henderson slowed down and stopped when he saw Chet’s car on the side of the road.

“Flat tire, huh,” he said. Buster bounded out of the police car, as always at Henderson’s uniformed side.

“Of course it’s a flat tire,” Jan spat out. “Any effing idiot can see we have a flat tire.”

Henderson blinked, surprised at the foul word escaping Jan’s lips. He’d never heard her swear before. “Need some help?” he asked Chet.

“I’ve got it. You might wanna take Jan and Billy ahead to the party, though.”

“Maybe I’d rather be asked before you made any decisions for me,” Jan bitched.

Henderson flinched at the edge to her voice. Chet shrugged, Jan swore again, and Henderson turned toward his son, who had just noticed him.

“Dad! Dad, you’re here!” Billy stood up from the ground where he’d been picking up rocks and throwing them into the quarry when Buster’s nose and ears twitched.

That twitch mean trouble in ‘Nam, meant trouble anywhere.

“Freeze, son!” Henderson ordered, his voice raw. “Don’t move!”

Billy froze, his face crumpling into worried lines at his father’s harshness.

“Don’t move,” Henderson repeated, reaching for Buster’s leash.

With a mother’s instinct and memories of post-war days before she’d divorced, Jan screamed. Chet grabbed what was left of her waist and clamped a hand across her mouth.

“Don’t cry, don’t talk, don’t make a sound,” Henderson said, keeping his voice low. “We’ve got an explosive device around. Billy, stay still for Daddy.” He registered that it was the first time he’d ever referred to himself as Dad for anyone but Buster. “Let Daddy and Buster come get you.”

Jan gasped behind Chet’s hand, as Henderson’s hand motioned…

“Buster–Advance.”

The Double-D advanced. Memories of the smell of gunpowder and blood mingled with memories of baby Billy crawling and licking his hand. The sweet loving look on the old Jan’s face mingled with the terrified look on Billy’s face now. The stink of the stagnant water inside the quarry reminded him of rice paddies filled with human excrement and rotting fish fertilizer. Only the shining sun on a boy’s birthday contrasted with the dark memories of the Kong’s black, root-bound tunnels.

Buster took his time, his canine senses concentrating on the job with familiarity. For the first time, Henderson couldn’t. His hands sweat, his mouth dried, and he suddenly remembered he hadn’t spoken his old magic chant; the same chant he continued to whisper in police uniform before every job. Too late now. Buster was inches away from Billy when he stopped, motionless, his canine nose pointing at the tiniest end of an ancient quarry blasting cap protruding from the wind-swept ground.

“Got it, Buster,” Henderson whispered. “Good boy, Billy, for not moving.” Henderson stroked his son’s cheek. “That’s my brave birthday boy.” He tenderly picked up the child, carried him back a good ten feet from the cap before putting him down, then pressed Buster’s leash into Billy’s hand, and whispered.

“Go as slowly, as quietly as you can back to your mother. Tell her I said for all of you get in the car and drive to the party. Buster, too. Do not slam the doors. Be very quiet. Take care of Buster ’til I get back. Nod if you understand me.”

Billy nodded, his eyes round and wide and frightened. He reached up for Henderson, who shook his head and refused to lift the child into his arms. “Obey me, son. Now.“

Billy backed up. Henderson motioned a reluctant Buster to do the same with an old ‘Nam hand signal, carefully watching until they were all inside the car. He saw Chet quietly half-latch the open door. Buster whined in frustration, but couldn’t escape the back seat. Henderson took in the black and tan head, and suddenly noticed the gray fur under the jaw. When had that happened?

He saw Jan’s face; realized she still loved him, couldn’t help but love him, and hated him for it. His gaze slid to his son in Jan’s arms, the child’s hand still holding tight to Buster’s leash. Father’s and son’s glance met. Henderson smiled, and mouthed to Billy, It’s okay. It’s okay.

Henderson bent to the blasting cap, thanking God he always carried the most basic of tools on his person. They never left him, just like his gun never left him, not in ‘Nam, not at home. He turned back for a minute to see Buster’s nose pressed against the window, and smiled again.

That’s one vow I kept. Didn’t help with the farm like I promised my family. Didn’t keep my wedding vows. Sure wasn’t much of a father, either. But I’ve been a decent soldier. Swore I’d never leave my best buddy behind. Promised Buster he’d be taken care of. At least I kept one of my promises.

Henderson was still smiling when the police radio he’d forgotten to turn off crackled to life. The frequency activated the blasting cap attached to an old stick of dynamite hidden beneath the soil. The explosion blew shrapnel into Henderson, then blew his still-twitching body into the dark paddy that was the bottom of the quarry.

The Army Reserve and most of Henderson’s old VA counseling buddies joined the police department in uniform at the late afternoon funeral. Inside the church, Billy stood straight and tall in his new black suit. It looked well against the tan and black of K-9 Buster, now officially retired. Boy and dog led the procession of mismatched pallbearers carrying the mercifully closed coffin to the front of the aisle. The left half of the coffin’s bearers wore police uniforms. The right half consisted of the Latino in his Army dress uniform, and the Apache and Quiet Kid in suits. Jan sobbed next to Chet in the front pew, one hand on her pregnant belly, the other holding the picture frame showing the old Army photo of Henderson and Buster in country. She insisted it be placed on the resting coffin.

The Latino did so for her. The honor guard then sat down.

“Another dead dogface,” a much younger cop whispered to the vet. “Too bad it wasn’t the mutt.”

The Latino’s look of withering scorn had the younger pallbearer cringing. Both remained silent for the rest of the service, and throughout the burial in the special veteran’s section at the small cemetery that had been the final resting place for farmers–and farmers killed in war–for generations.

The police honor guard folded the flag and started to pass it to Henderson’s mother. Billy cut in front of her, and took the flag himself. Flag in one hand, Buster’s leash in the other, Billy listened as Henderson’s grandfather, a WW2 vet, played taps on his old bugle. The sound of the notes rippling through the open fields of amber grain gave almost everyone present gooseflesh, as did the gun salute. When Buster lifted his nose high to howl his death keen, even the most hardened of men lost it. Through it all Billy remained silent and upright.

He continued to stand at the grave long past what was considered normal. First Chet, then Jan told him the honor guard wouldn’t leave the gravesite until the family did. Billy shook her off. The three from Henderson’s old unit moved protectively around the child. He continued to stand at attention until the evening sunset and then beyond. With a farmer’s eye for weather and detail, the child watched the sky, the trio surrounding him just as motionless as boy and canine.

Only when the brightness of Sirius, the Dog Star, appeared in the heavens did the legacy of Henderson’s kept promise pivot on black loafers and blacker paws, and all head for home.

Vietnam was the last war where USA policy dictated that military war dogs be left / destroyed overseas. Now, ALL war dogs are guaranteed BY LAW a trip home for further service, retirement, and/or adoption.

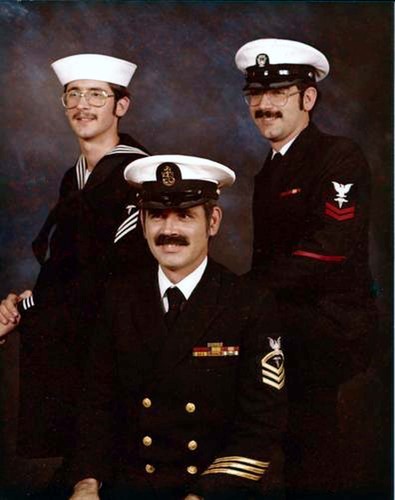

My father, husband & brother-in-law all served in the military.

My USAF father flew with a helicopter squadron for TWO tours of ‘Nam duty,

My USN corpsman husband served during ‘Nam in a stateside hospital,

And my brother-in law was a USN corpsman attached to ‘Nam river patrol boats.